How can Oceanic perspectives on climate justice inform global action on climate change?

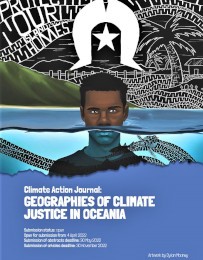

In this blog, Prof. Susan Harris Rimmer, an international human rights lawyer and the Director of the Griffith University Policy Innovation Hub, and the Climate Justice theme leader of the Griffith Climate Action Beacon, discusses how Oceanic perspectives on climate justice can inform global action on climate change. Prof. Rimmer is also one of the Guest Editors of Climate Action’s upcoming topical collection: Geographies of climate justice in Oceania.

How should climate justice be defined

from (an) Oceania perspective(s)?

from (an) Oceania perspective(s)?

The challenge of defining climate justice is to take the principles of justice that look to support both individual rights and the capacity of people to flourish with their communities and then to 1) extend these, with modifications to both other species and future environments and 2) to ensure their applicability as we transition and adapt, understanding the existing injustices can render some people more vulnerable to the adverse impacts of these processes. In other words, we need to develop a set of ideas about justice in the era of climate change that will help us build institutions, design and deliver projects and policies that will foster just processes and outcomes in climate change transitions, both for ourselves, other species, future generations and some would argue, the land itself.

How can Oceanic perspectives on climate justice inform global action on climate change?

Oceanic perspectives are extremely diverse, and include First Nations wisdom. Climate change is the most significant contemporary future threat facing the global community but many impacts are hitting Oceania first. The transboundary and multidimensional nature of climate impacts mean that any effective responses require collective, multi-stakeholder policy engagement underpinned by diplomatic process and practice, and Oceania has skill and practice to share in climate diplomacy.

‘Climate diplomacy’ encompasses the set of practices, procedures and protocols through which sovereign nation-states advance and negotiate their interests relating to a changing climate, with other states and global actors. In this context, diplomatic efforts on the part of states within international relations are assumed to be done to advance the interests of the peoples on whose behalf the states and other actors claim to act. Much of this activity is largely undertaken within an institutional system established under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC); a system that is designed to foster consensus-based agreement among member states. Most recently centred on negotiation and implementation of the 2015 Paris Agreement, the global climate regime also incorporates a series of protocols which establish obligations on parties to the Framework. The diplomatic activity associated with the UNFCCC has given rise to distinct sets of political issues and agendas, as well as specialised forms of practices, procedures, language and protocols that have come to define and delineate the practice of ‘climate diplomacy’. These are further underpinned by diversity of worldviews, values and aspirations, and have led also to increasing number of coalitions to impact the international UNFCCC agenda and its priorities.

Importantly though in today’s deeply interconnected world the emerging practice and patterns of climate diplomacy interact across a range of wider range of political interests and policy domains, including: i) international relations; ii) trade, investment and business; iii) development; and iv) security (traditional and non-tradition), advanced by state and non-state actors through a multitude of bilateral and multilateral arenas. Understanding how climate interests are identified, advanced and contested by different actors across the broader diplomatic landscape is of emerging significance for scholars and practitioners alike.

As a founding member of the climate diplomacy regime, Australia has an enduring, though uneven history of engagement in climate diplomacy spanning three decades. Special Ambassador for the Environment (with responsibility for climate change) has been a special thematic appointment within Australia’s diplomatic service since 1989, with eleven appointments to the role having been made since that time. While the politics of Australia’s positioning on climate change has attracted significant discussion, the history and nature of diplomatic interactions remains underexplored, and provides an important pivot point for this research program. And yet, Australia’s positioning cannot be examined in isolation from its regional counterparts, particularly in the Pacific, where the impacts of a changing climate have a disproportionate impact on island states themselves.

Pacific island nations have a direct and abiding stake in global efforts to mitigate climate change and international cooperation intended to help communities adapt to its impacts. Over past decades they have engaged diverse strategies, including the formation of enduring coalitions with other countries – namely the Alliance of Small Island States (formed in 1990) and more recently the ‘High Ambition Coalition’ (2015) – to exert considerable influence in global climate talks. Working through these coalitions, Pacific island states have been decisive in the design of key agreements, including the 1997 Kyoto Protocol and the 2015 Paris Agreement. Pacific leadership of the climate diplomacy agenda is deserving of attention as we conceptualise the nature of climate diplomacy, and offers important lessons for policy and decision-makers across the Asia-Pacific region, particularly in Australia.

Over the past two decades we have seen a proliferation of non-state actors, groups and constituencies engage in multilateral negotiations, engaging in forms of diplomacy that are intended to advance interests that are not or cannot be represented by sovereign states. These groups include, inter alia, cities, local communities, social movements, Indigenous peoples, migrants, refugee and their advocates, Non-Governmental Organisations, regional multilateral and civil society organisations, and innovative, issue-based coalitions (such as the Friends of the Ocean). Not only are these non-state actors engaging in important forms of diplomacy to elevate excluded interests into the formal mechanisms of multilateral decision making, they are also playing a part in reshaping the discursive, normative and epistemic parameters of collective action on climate change.

There is important and ongoing research to be done on understanding how state and non-state actors represent themselves and their interests in the global landscape, and how their diplomatic efforts offer new ways of thinking about and acting upon climate change. By bringing the distinct yet interdependent experiences and interactions of Australia and Pacific island state and non-state actors to the fore, this research program offers significance for the theoretical framing of climate diplomacy and opportunities to improve practice into the decades ahead. It is significant because it aims to develop a better understanding of how diverse interests can be negotiated and pursued when consensus may not be possible due to the incommensurability of different worldviews, normative commitments, values, and conceptions of (climate) justice.

Drawing on what Hsu et al. (2015)1 call ‘a new climate diplomacy’, it explores how Pacific civil society actors are pursuing climate justice through their engagements with nation-state and international institutions in formal sites of climate diplomacy. Adopting a critical, interpretivist approach, and utilising qualitative methods, we examine how Pacific civil society actors challenging the established diplomatic conventions in multilateral climate governance by advancing Indigenous and relational perspectives on the process and substance of climate diplomacy. A key focus in this project will be on how justice-oriented listening cultures can be embedded in climate diplomacy.

While we often think about diplomacy as involving speaking at the right time, and in the right way, to the right people, we often fail to consider the importance of listening to practices of diplomacy in negotiating just climate futures. As Susan Bickford suggest, “a particular kind of listening can serve to break up linguistic conventions and create a public realm where a plurality of voices, faces, and languages can be heard and seen and spoken (Bickford 1996: 129). As new climate diplomacy actors come on to the scene, it is important that institutional arrangements and diplomatic actors can accommodate the plurality of voices, perspectives and worldviews that demand to be heard in their pursuit of climate justice. This study will explore how heterodox listening frameworks can be brought to bear on the task of transforming listening cultures in international climate diplomacy, and how such different practices can support an inclusive environment for negotiating just climate action.

1A. Hsu et al. (2015) Towards a new climate diplomacy. Nature Climate Change https://www.nature.com/articles/nclimate2594

Read more blogs and selected research collections in our SDG13 hub.

Starting January 2022, corresponding authors affiliated with 47 universities in Australia and New Zealand, or at one of the seven additional participating institutions in the region, can publish their article OA with fees covered, in more than 2,000 Springer hybrid journals. Find out more about your eligibility

About the author

Professor Susan Harris Rimmer is an international human rights lawyer and the Director of the Griffith University Policy Innovation Hub (appointed July 2020), and the Climate Justice theme leader of the Griffith Climate Action Beacon. Sue has been named a Top Innovator for her project the Climate Justice Observatory with Uplink at the World Economic Forum and is a 2022 Fulbright Scholar. Susan is the co-editor of the Futures of International Criminal Justice (Routledge 2022, with Emma Palmer, Edwin Bikundo and Martin Clark), the Research Handbook for Feminist Engagement with International Law (Edward Elgar 2019, with Kate Ogg); and the author of Gender and Transitional Justice: The Women of Timor Leste (Routledge, 2010) plus over 40 refereed academic works.